DNA Fingerprinting Definition

DNA fingerprinting – sometimes called “DNA testing” or “DNA profiling” – is a method used to identify living things based on samples of their DNA.

Early DNA fingerprinting was developed in the years before the whole human genome had been sequenced. Instead of looking at the whole sequence of a person’s DNA, these techniques look at the presence or absence of common markers that can be quickly and easily identified.

The best markers for use in quick and easy DNA profiling are those which can be reliably identified using common restriction enzymes, but which vary greatly between individuals.

For this purpose, scientists use repeat sequences – portions of DNA that have the same sequence so they can be identified by the same restriction enzymes, but which repeat different numbers of time in different people.

Types of repeats used in DNA profiling include Variable Number Tandem Repeats (VNTRs), especially short tandem repeats (STRs), which are also referred to by scientists as “microsatellites” or “minisatellites.”

The term “satellite” may seem confusing – it comes from the fact that, when DNA is centrifuged, these “satellite” repeating regions float above the rest of the DNA.

By looking to see how many copies of each VNTR a person possesses, scientists can “fingerprint” them with a high degree of accuracy.

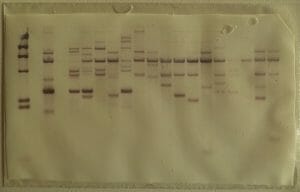

A DNA fingerprint looks something like the columns on the paper below. On this paper, each dark band represents a fragment of VNTRs – and each column is a different tissue sample. A match would be indicated by two columns whose VNTRs patterns matched precisely.

DNA fingerprinting is different from genetic testing, in which a DNA sample is tested to see if it contains genes for inherited diseases or other traits.

Function of DNA Fingerprinting

DNA fingerprinting is frequently used in criminal investigations to determine whether blood or tissue samples found at crime scenes could belong to a given suspect.

This technology is also used in paternity tests, where comparison of DNA markers can show whether a child could have inherited their markers from the suspected father.

In science, DNA fingerprinting is used in the story of plant and animal populations to determine how closely related species and populations are, and to track their spread over time.

This ability to look directly at an organisms’ gene markers has revolutionized our understanding of zoology, botany, agriculture, and even human history.

DNA Fingerprinting Steps

Extracting DNA from Cells

To perform DNA fingerprinting, you must have a DNA sample!

In order to procure this, a sample containing genetic material must be treated with different chemicals. Common sample types used today include blood and cheek swabs.

These samples must be treated with a series of chemicals to break open cell membranes, expose the DNA sample, and remove unwanted components such as lipids and proteins until relatively pure DNA emerges.

PCR Amplification (Optional)

If the amount of DNA in a sample is small, scientists may wish to perform PCR – Polymerase Chain Reaction – amplification of the sample.

PCR is an ingenuous technology which essentially mimics the process of DNA replication carried out by cells. Nucleotides and DNA polymerase enzymes are added, along with “primer” pieces of DNA which will bind to the sample DNA and give the polymerases a starting point.

PCR “cycles” can be repeated until the sample DNA has been copied many times in the lab, if need be.

Treatment with Restriction Enzymes

Once sufficient DNA has been isolated and amplified if necessary, it must be cut with restriction enzymes to isolate the VNTRs.

Restriction enzymes are enzymes that attach to specific DNA sequences and create breaks in the DNA strands.

Bacterial cells use restriction enzymes for protection against DNA viruses which may invate the cell and hijack its machinery – but scientists have taken advantage of these special enzymes and used them to make DNA profiling and even genetic engineering possible.

In genetic engineering, DNA is cut up with restriction enzymes and then “sewn” back together by ligases to create new, recombinant DNA sequences.

But in DNA profiling, only the cutting part needs to happen. Once the DNA has been cut to isolate the VNTRs, it’s time to run the resulting DNA fragments on a gel to see how long they are!

Gel Electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis is a brilliant technology that separates molecules by size. The “gel” in question is a material that molecules can pass through – but only at a slow speed.

Just like air resistance slows a big truck more than a motorcycle, the resistance offered by the electrophoresis gel slows large molecules more than small ones. The effect of the gel is so precise that scientists can tell exactly how big a molecule is by seeing how far it moves within a given gel in a set amount of time.

In this case, measuring the size of the DNA fragments from the sample that has been treated with restriction enzyme will tell scientists how many copies of each VTNR repeat the sample DNA contains.

It’s called “electrophoresis” because, to make the molecules move through the gel, an electrical current is applied. Because the sugar-phosphate backbone of the DNA has a negative electrical charge, the electrical current tugs the DNA along with it through the gel.

By looking at how many DNA fragments the restriction enzymes produced and the sizes of these fragments, the scientists can “fingerprint” the DNA donor.

Transfer onto Southern Blot

Now that the DNA fragments have been separated by size, they must be transferred to a medium where scientists can “read” and record the results of the electrophoresis.

To do this, scientists treat the gel with a weak acid, which breaks up the DNA fragments into individual nucleic acids that will more easily rub off onto paper.

They then “blot” the DNA fragments onto nitrocellulose paper, which fixes them in place.

Treatment with Radioactive Probe

Now that the DNA is fixed onto the blot paper, it is treated with a special probe chemical that sticks to the desired DNA fragments. This chemical is radioactive, which means that it will create a visible record when exposed to X-ray paper.

This method of blotting DNA fragments onto nitrocellulose paper and then treating it with a radioactive probe was discovered by a scientist name Ed Southern – hence the name “Southern blot.”

Amusingly, the fact that the Southern blot is named after a scientist has nothing to do with directions didn’t stop scientists from naming similar methods “northern” and “western” blots in honor of the Southern blot.

X-Ray Film Exposure

The last step of the process is to turn the information from the DNA fragments into a visible record. This is done by exposing the blot paper, with its radioactive DNA bands, to X-ray film.

X-ray film is “developed” by radiation, just like camera film is developed by visible light, resulting in a visual record of the pattern produced by the person’s DNA “fingerprint.”

To ensure a clear imprint, scientists often leave the X-ray film exposed to the weakly radioactive Southern blot paper for a day or more.

Once the image has been developed and fixed to prevent further light exposure from changing the image, this “fingerprint” can be used to determine if two DNA samples are the same or similar!

Quiz

1. Which of the following is NOT a use of DNA profiling?

A. Determining if two DNA samples come from the same person.

B. Determining if a child could have inherited their genes from a suspected father.

C. Determining whether a person has a given genetic disease.

D. None of the above.

2. You have a DNA sample that you need to profile, but the amount of DNA is so small that you’re concerned the results might not be clear. What do you do?

A. Use extra radioactive chemicals on the Southern blot.

B. Use PCR to create copies of the DNA sample before running the electrophoresis.

C. Expose the X-ray for a week instead of a day at the end of the process.

D. All of the above.

3. Which of the following would result in an inaccurate or unusable DNA profile if it happened during the profiling procedure?

A. Skin cells from an investigating policeman get into the DNA sample from a crime scene before the sample is run.

B. The restriction enzymes had expired and did not work on the sample.

C. The power went out before the electrophoresis procedure was finished.

D. All of the above.

Reference

- Tautz, D. (1989). Hypervariabflity of simple sequences as a general source for polymorphic DNA markers. Nucleic Acids Research, 17(16), 6463-6471. doi:10.1093/nar/17.16.6463

- A. (2015, March 31). A beginner’s guide to DNA fingerprinting. Retrieved May 11, 2017, from http://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/press/for-journalists/code-of-a-killer-1/a-beginners-guide-to-dna-fingerprinting

- DNA migration in gel electrophoresis. (n.d.). Retrieved May 11, 2017, from http://scienceprimer.com/dna-migration-gel-electrophoresis

DNA Fingerprinting

No comments:

Post a Comment